Last Updated on 2021 年 07 月 24 日 by 編輯

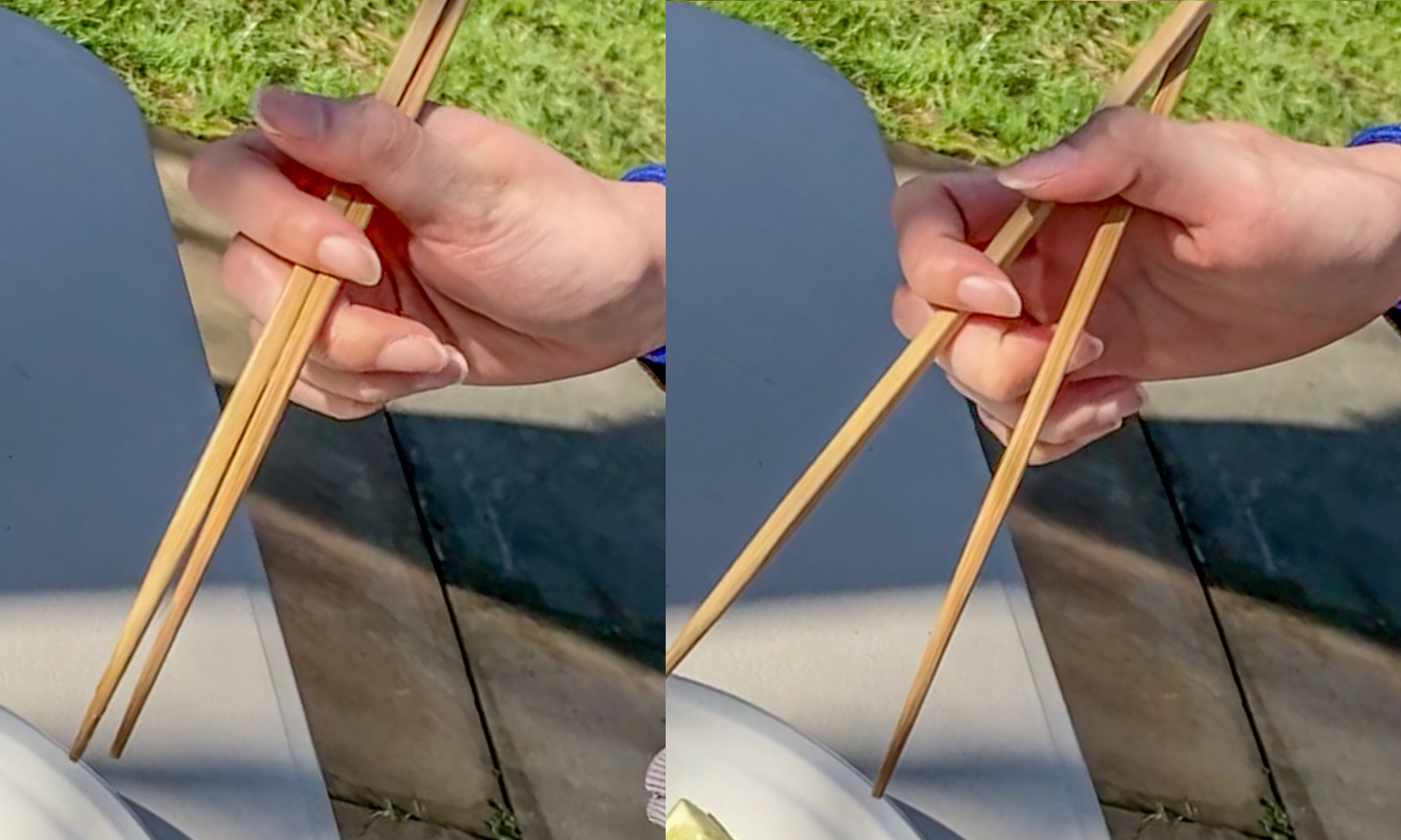

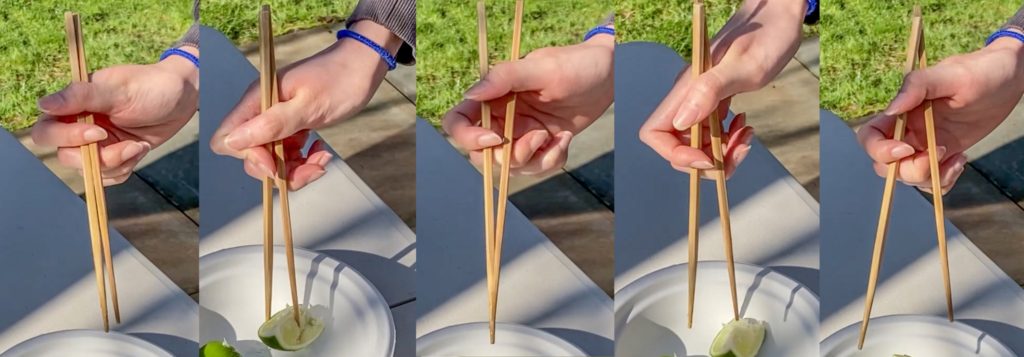

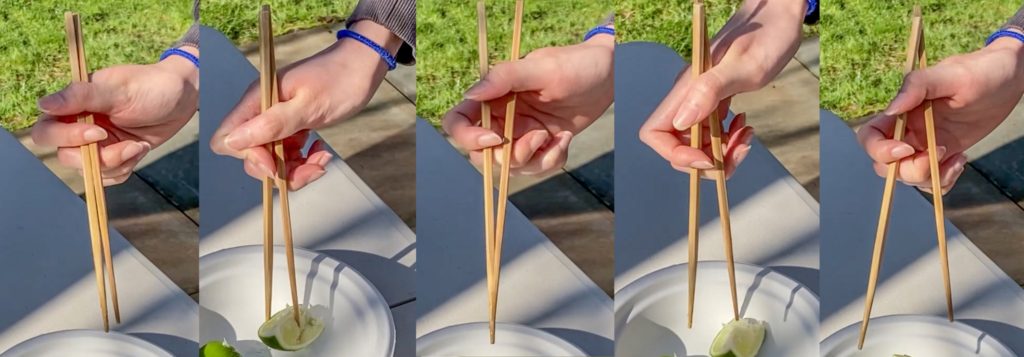

Variant grips of the Lateral family abound, as discussed in Lateral chopstick grips. But only one can be the stereotypical grip of this family, the classic-swing one. We call this stereotypical grip the Lateral Classic. And the “type species” of Lateral Classic is the Lateral Chick. Key postures of this grip are shown below. From left to right, they are: 1) Abutting posture, 2) Compression posture, 3) Closed posture, 4) Open posture, and 5) Max open posture.

This article identifies a few variants of Lateral Classic, covering common patterns mastered by practitioners. These have been aliased Lateral Chick, Lateral Squid, and Lateral Gangnam Style, based on the the form taken by the hand, as it pries open chopsticks to extend tips apart.

內容目錄

Why “lateral”

While grips in the Lateral family vary greatly in how they work when extending tips of chopsticks open, all of them share one common finger posture when a practitioner compresses two chopsticks to pick up food. We call this the “compression posture”, and it is shown below.

As the Lateral family article documents, the name “lateral” is borrowed from an identically-looking penhold called Lateral Tripod, shown below right.

All Lateral chopstick grips also share a similar look to the Righthand Rule chopstick grip, shown above left. But note how Lateral Classic chopstick grip has the tip segment of the thumb lying on the lateral side of the index finger, unlike Righthand Rule where the thumb tip actively operates the top chopstick. This disuse of the thumb tip in Lateral Classic results in a completely different biomechanics for fingers, when compared to Righthand Rule. We shall shortly explain.

Why “classic”

The name “Classic” in Lateral Classic refers to the way the top chopstick is swung open, in this grip. In a “classic swing”, the top chopstick is extended upward by the practitioner. This is one of three types of swings documented in the article Out with the Crossed Type, in with the Under Swing. This “classic swing” can be observed in the following video.

Key postures of this video are shown below again, for reference. From left to right, they are: 1) Abutting posture, 2) Compression posture, 3) Closed posture, 4) Open posture, and 5) Max open posture.

Clutching sticks closed

Variants of the Lateral family all sport their own unique ways of extending tips of chopsticks open. But all variants employ one common way to close tips of chopsticks to pick up food. Lateral Classic is no exception.

Like all variants, Lateral Classic simply “clutches” the two chopsticks, and uses the hand to squeeze them until they abut each other. This is shown below. Observe how middle sections of the two sticks in all three pictures “rest” on the middle finger. Their rear ends rest on the purlicue, the webbed part between thumb base and index finger. These two chopsticks slide on the middle finger, towards each other, as they are squeezed closed by the base of the thumb from one side, and by the curled index finger from the other side.

We call the posture where fingers bring two chopsticks as close as possible to each other, the Abutting posture. While all Lateral practitioners can easily clutch sticks into this posture, they almost never do so in real life. In fact, many Lateral practitioners go out of their way to avoid ever getting chopsticks into this posture – some Lateral practitioners find it hard to separate the two chopsticks, once they come to abut each other as shown above right.

Picking up food

In most eating situations, practitioners don’t bring two chopsticks to abut each other. Instead, they bring tips of chopsticks together, to sandwich a piece of food. This is shown below. We call this the Compression posture, because the practitioner needs to exert enough compression force on chopsticks, in order to grasp a piece of food securely.

The Compression posture shown above right indicates this “compression” in action. Note how the pad of the index finger pushes down on the top chopstick, and also how the base of the thumb pushes up on the bottom chopstick. Tension exerted by muscles can be observed in the picture shown above right.

This is still the same “clutching” action from the previous section. However, a piece of payload sits in between tips of chopsticks. So the two sticks cannot come together completely, at their tip sections. Instead, they abut each other only at their rear ends. The two sticks form a triangle, with the payload serving as a third side. This triangular shape is also a hallmark of all Lateral grips.

Picking up food with Standard Grip

Many alternative grips make use of the thumb pad, unlike Lateral grips. Thumb-using grips sport a different look, at the Compression posture. Following pictures illustrate the same three postures from earlier, but this time with a practitioner wielding Standard Grip.

Compare the Open posture and the Compression posture to their Lateral counterparts from earlier. The two chopsticks in Standard Grip still form two sides of a triangle, but the pointy end of the triangle is no longer at the rear.

The stark contrast between Lateral grips and Standard Grip are shown again below, for a direct comparison. At the Compression posture, chopsticks in Lateral Classic taper towards the rear end. But chopsticks in Standard Grip are separate far apart, at the ear end. The two sticks taper towards the front instead, forming a pointy end at the tips where a payload is sandwiched.

Ramifications of this difference will presently be discussed.

How food slips away

Take a look at the three video clips shown below. The left two are Lateral Classic. The right one is Lateral Turncoat, a related grip, and the topic of a different article. But they are shown together, because they share one thing in common, when they pick up food. Note how every Lateral grip practitioner twists her wrist 90°, right after securing a payload between tips of chopsticks. That is, they tilt their chopsticks, turning stick orientation from vertical to horizontal.

Now, take a look at how Standard Grip picks up food again. The practitioner does not feel an urge to twist his wrist, to level chopsticks. Instead, he lets the payload remain at the bottom, caged between chopstick tips. Then he simply raises his arm to lift the payload. He leaves his chopsticks pointing down in the same orientation throughout the lifting maneuver.

It is true that in almost all cases, to feed oneself, one must eventually tilt chopsticks upward. It can be quite ungainly to try to bring a piece of food to the mouth, with chopsticks pointing downwards. So in eating situations, the wrist has to turn 90° sooner or later, to bring food to the mouth.

For many alternative grips such as Standard Grip, the practitioner has an option of making this tilt early on, when they lift up food, or later on, when they bring it to the mouth.

However, for Lateral grip practitioners, including Lateral Classic, this may not be a choice. Most Lateral practitioners are subconsciously programmed to make this wrist twist as soon as they secure slippery food, from years of experience.

One reason for this is the triangular shape formed by the two chopsticks and the payload, which we’ve discussed in the last section. With a leverage of this kind, securing slippery food such as a slice of lime is no easy task. The harder a practitioner squeezes chopsticks closed, the more likely the two chopsticks would push the payload forward and out of the grasp of chopstick tips. When chopsticks are pointing downward, then gravity exacerbates this tendency of payload to fall off chopsticks.

Tilting chopsticks upward neutralizes this threat. Now, gravity isn’t pulling the payload out of the widening (non-)grasp of chopstick tips. If chopsticks tilt beyond 90°, then gravity may even assist with grasping, by dragging the payload towards the hand, instead of away from it. Sometimes a practitioner may orient their hand such that the payload sits on one stick, for an even better leverage, as shown below left.

On the other hand, for Standard Grip, the harder the hand clamps down on the payload, the more likely the payload is to get pushed upward towards the hand, due to the angle of chopsticks. This upward push counters the effects of gravity on the payload. This is one reason why Standard Grip practitioners are not in a hurry to tilt chopsticks upward.

With that said, in most situations, food items are not hard nor smooth, and do not present a slimy surface to the practitioner. Lateral Classic practitioners are able to lift off food vertically, when picking up most regular food items. This is shown below.

Extending tips apart

While the Compression posture for all Lateral grips look the same, every variant in the Lateral family sports its own unique finger dynamics for extending tips of chopsticks apart. Even within the same Lateral Classic grip, different practitioners employ their own personal finger movements. We name a few common variants with aliases that take after the form of the hand seen at the Open posture.

Lateral Chick

Here is how one practitioner extends chopsticks apart. We call this Lateral Chick.

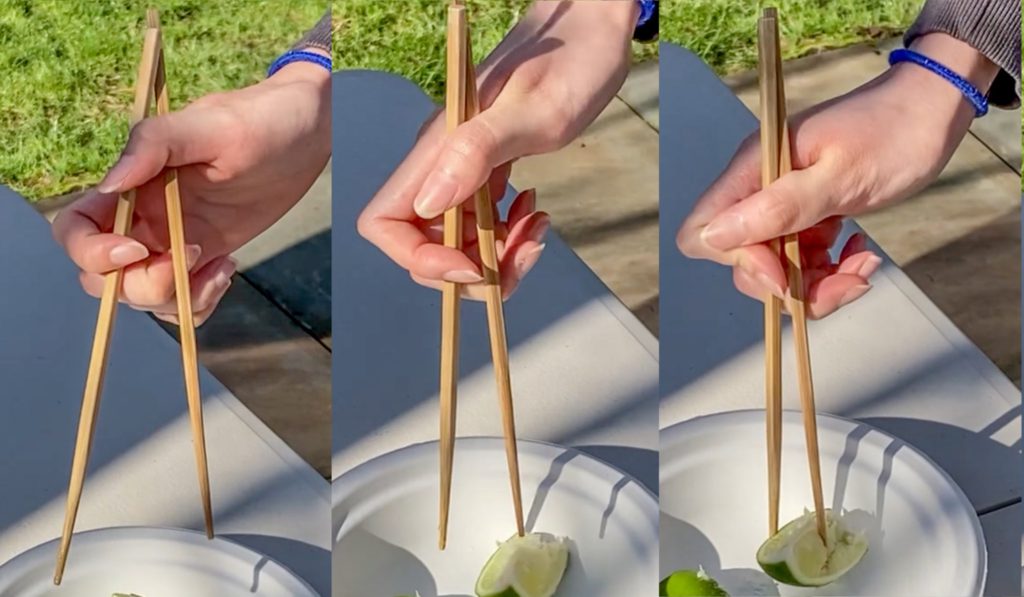

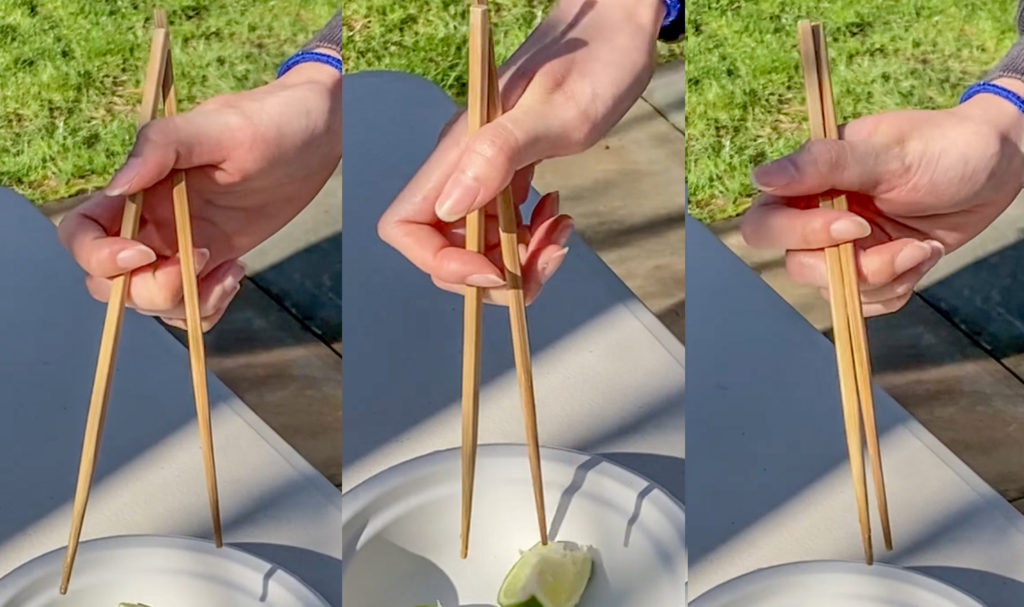

Key moments are shown below. Note how the bottom chopstick remains in the same place from the first moment through the last moment. It is held immobile by the base of the thumb which remains fixed in place together with the palm. Observe how the rest four fingers move away from the palm in synchrony, with the index finger and the middle finger caging and dragging the top chopstick away with them.

If this movement is exaggerated further, this grip could transform into Chicken Claws, shown below center. The introductory article Lateral chopstick grips described this relationship further. This is why the variant is named Lateral Chick. Yet another possible exaggeration of this movement is the Dangling Stick grip, shown below right.

Lateral Squid

Here is a milder form of Lateral Classic. The two chopsticks are not extended apart as much as the previous practitioner did. And completely different finger movements are employed to extend chopsticks apart. All five fingers flex, in a way that look like pulsing squid tentacles. Thus the alias Lateral Squid.

This chopstick move seems too magical to be real. Most readers will have a hard time replicating it. The following stop-motion video shows key frames in this movement, in stop-motion animation. The move starts with the Abutting posture, and ends with the Open posture. At a glance, it looks like the practitioner simply bumps the two chopsticks up, and they happen to fall back on the middle finger, now nicely extended apart.

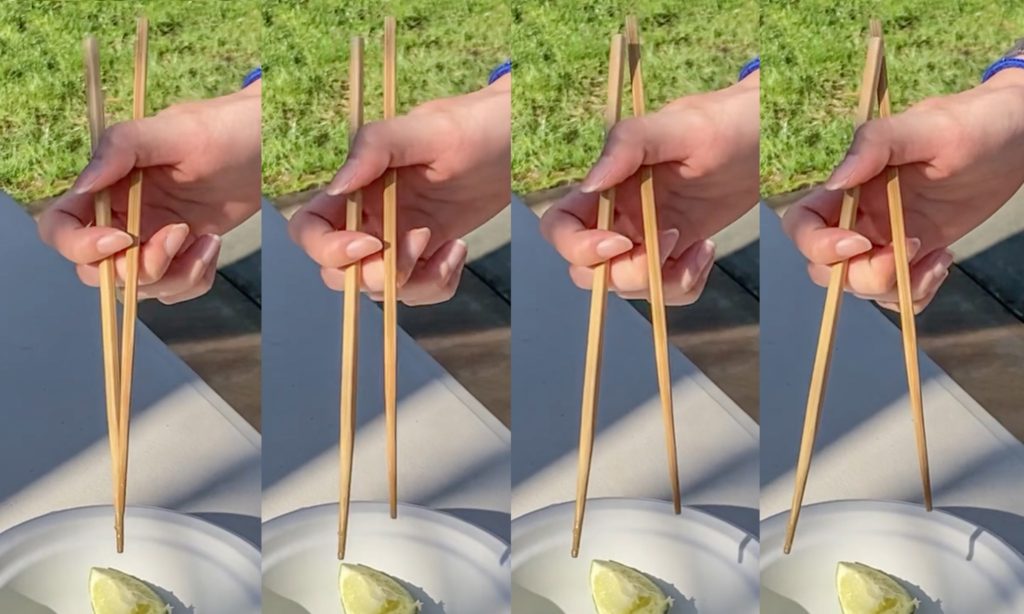

This move actually consists of two acts. The first act has the joint of the thumb work together with the of the middle finger, to roll the top chopstick away from the abutting configuration. If you watch the edges of the hexagonal top chopstick very carefully, you will see that it gets rolled for about 30° in the first act. This roll causes the chopstick to tilt out at the same time. This is the same planetary gear mechanism described in Planetary gears: physics of chopsticks. Key frames in the first act are shown below.

Once there exists a small gap between the two chopsticks, then the second act begins. Now the base of the thumb works with the same middle finger knuckle to sandwich, instead, the bottom chopstick. They hold the bottom chopstick immobile. The thumb joint now nudges the top chopstick away from the bottom chopstick which is held immobile. When the top chopstick slides past and clears the middle finger knuckle, the move is complete.

The same tip extension move can be observed in the following two videos as well, where the practitioner picks up a piece of food. Lateral Squid is among the hardest chopstick grips to master.

Following is a summary of key postures in Lateral Squid.

Finally, let’s look at this grip alongside a short video clip of a squid from Feeding Time for the Squid from Erick Tseng.

Related grip: Lateral Turncoat

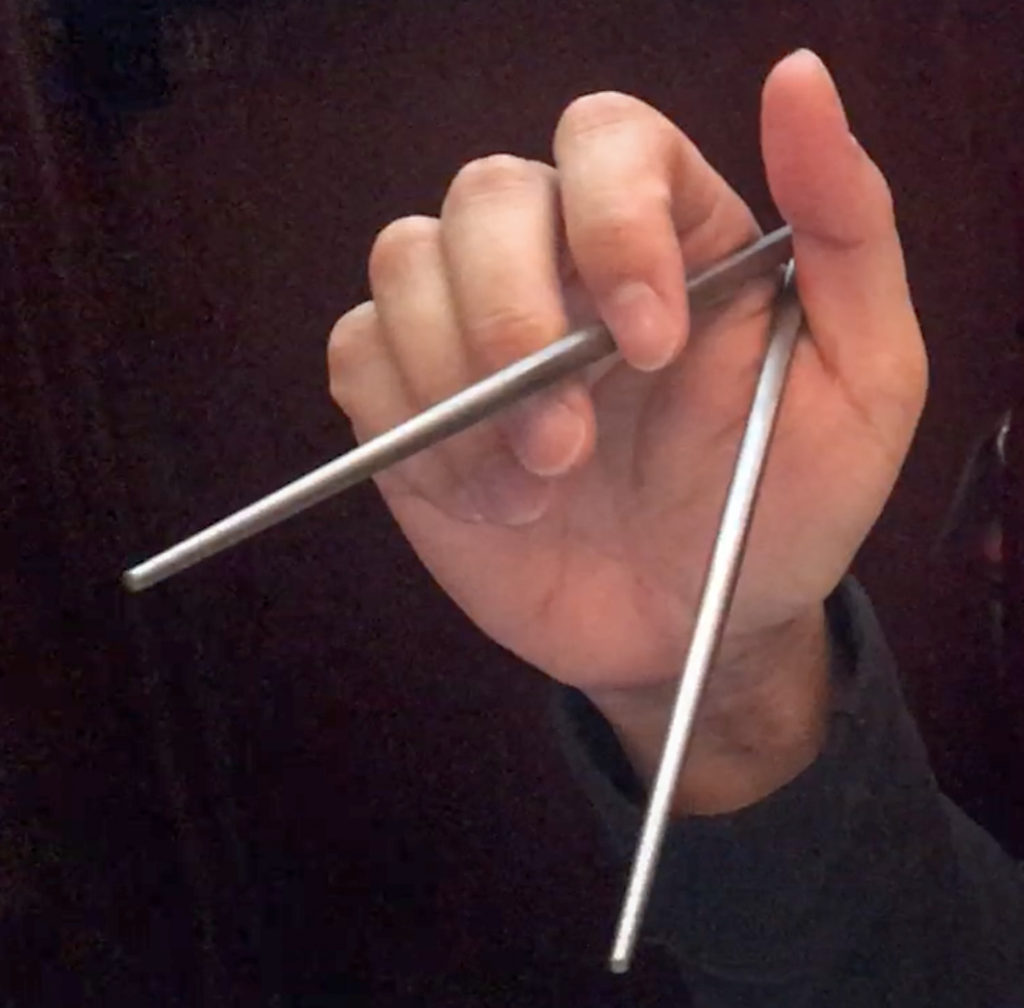

A related grip almost looks the same as Lateral Classic. It called Lateral Turncoat, and is shown below. Carefully follow the thumb tip and the middle finger in the four postures. Note how the tip segment of the thumb changes from unused on the far left, to being instrumental in holding the top chopstick on the far right. Also note how the tip of the middle finger braces against the top chopstick, as the thumb prods the top chopstick up.

This variant is the only Lateral grip which does make use of the tip segment of the thumb, when prying open chopsticks. As they say, the exception proves the rule. This is one such exception in Lateral grips. At the open posture and max open posture, Lateral Turncoat becomes a thumb-using grip. In fact, the open posture of Lateral Turncoat looks identical to the Turncoat grip. Thus the name of this variant.

The above difference notwithstanding, Lateral Turncoat is squarely a “classic swing” variant. But its use of the thumb tip in parts of the alternating motion sets it apart, and earns it a unique name.

Related grip: Lateral Gangnam Style

Below is yet another user wielding something that looks very similar to Lateral Turncoat. In this case, flat Korean chopsticks are used. These are much harder to use, compared to square chopsticks, as they are virtually impossible to roll. See the article on planetary gears about why rolling of chopsticks are important in chopsticking.

Just like sibling grips and cousin grips such as Lateral Turncoat, Lateral Chick and Lateral Squid, this one sports yet another unique way of extending tips of chopsticks, while sharing the same technique for Compression posture. The bottom chopstick is held immobile by the thumb base and the middle finger knuckle. The thumb joint and the index finger nudge and drag on the top chopstick to move it.

It is just different and special enough, that we gave this variant it own name: Lateral Gangnam Style. The way the thumb and the index finger dance around each other can only be described as “inspired” by the hand dance in the horse-ride move, from Gangnam Style.

Here is a quick reminder of said famous hand dance.

Following is a summary of key postures in Lateral Gangnam Style.

Update 2021-05: in popular culture

In May 2021 we analyzed an excellent episode on chopsticks and chopsticking by World Friends YouTube channel. We published a writeup of this review in YouTube episode on chopsticking from WorldFriends.

All three hostesses wield more than one chopstick grips. Two of three hostesses naturally use Lateral compression.

Jane extends chopsticks apart with Idling Thumb, but closes them against food items with Lateral compression. Sometimes she adopts Cupped Vulcan for extending chopsticks apart.

Hyejin believes that she primarily uses Scissorhand. But actual observations show that she switches to Lateral Thumb Wrestler as often as she uses Scissorhand. These two grips differ only in how they extend chopsticks apart. Both grips clutch chopsticks closed with the same Compression posture.

Near the end of the episode there was an amicable competition to see who could pick up jello without breaking them. It was stated in this segment, as well as earlier in the episode, that blunt chopstick tips worked better. In fact, Jane managed to pick up a piece of jello intact, with blunt ends of chopsticks. Blunt ends provide larger surface areas for gripping, enabling lighter compression forces from chopsticks to lift jello without slicing into them.

But there are additional factors at play here. The first is illustrated below. Note how Jane surrounds the jello with chopsticks pointing vertically down, at first. Then she gently nudges the piece of jello detached from the plate and its jello siblings. She accomplishes the feat by twisting her wrist, and thus tilting chopsticks slightly upward. This sequence of movements allows the two chopsticks to settle into said food item’s irregular and malleable surface, as the food item is wiggled in the process. This is a common technique among Lateral grip practitioners, and we documented earlier in this article.

We also have a sequence of Hyejin picking up noodles shown below. This is yet another Lateral compression grip. And she tilts chopsticks too in order to pick up noodles.

Yet another factor has to do with braking power. This is a topic we have not elaborated elsewhere on marcosticks.org. We only hinted at it in The Art and Science of Chopsticking:

We also emphasize extension power and chopstick reach. Because finesse comes as a balance of compression vs extension power. And precision is ironically a result of being able to command an expansive chopstick reach.

In order to pick up flimsy and pliable stuff like jello, a practitioner must apply enough force to firmly grasp it, but not too much as to break into it. Throughout the lifting process, fingers need to feel the texture of the food item via counterforces coming back from food surface. The practitioner must increase compression forces exerted by chopstick tips, or reduce them, at a blink of an eye as needed.

The trouble with the Compression postures of many chopstick grips, such as Lateral grips, is that they are only good at applying more and more compression forces by clutching fingers together. But they are not good at extending chopsticks apart. They are like a bikes without brakes. They can keep going faster and faster. But they can’t brake to reduce speed.

Jane is able to pick up jello, partially because she was wielding Idling Thumb. With this grip, the index finger and the middle finger cages the top chopstick firmly. These two fingers act like a brake. They are able to reduce compression forces on jello by slightly extending the top chopstick away. With this balance of compression vs extension power, she was able to applied just the right amount of force.

_____

* This practitioner is lefthanded. We have flipped his pictures to look righthanded, so that readers can compare different grips without having to mentally re-orient them.