Last Updated on June 30, 2021 by Staff

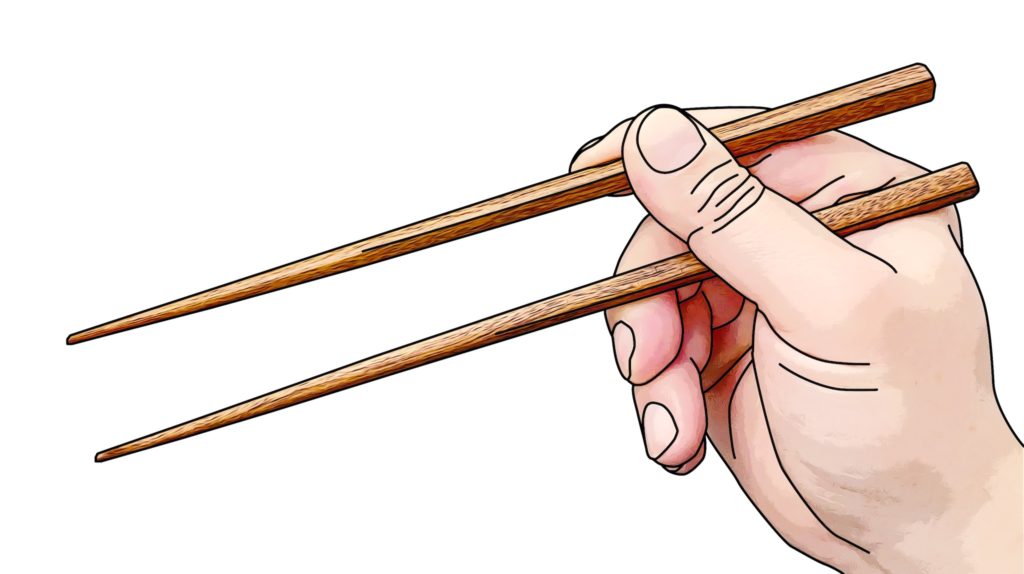

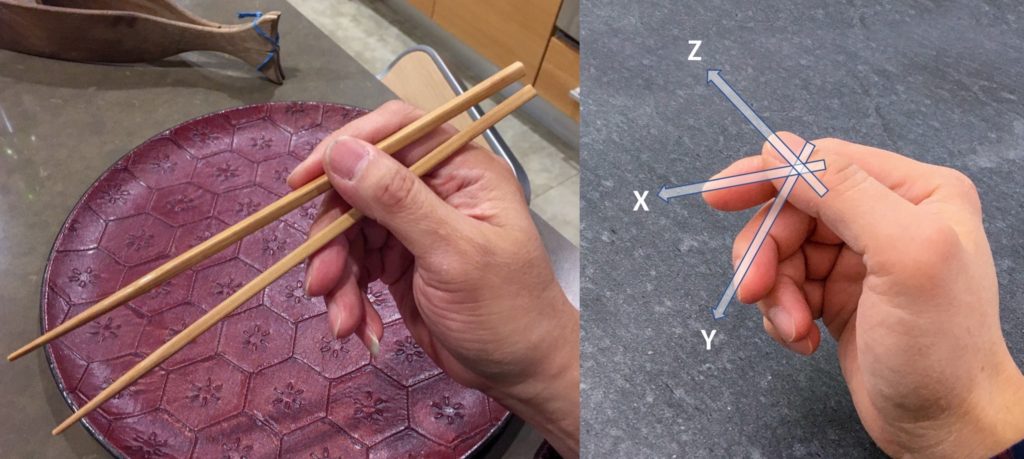

We named this alternative grip the “Righthand Rule” grip, after the right-hand rule used in mathematics and physics. The resemblance is obvious, as illustrated by the two pictures shown below.

Table of Contents

Righthand Rule vs. Standard Grip

The Righthand Rule grip (below left) looks very similar to Standard Grip (below right). The key difference is that users of Righthand Rule lower the distal knuckle of the middle finger, to take over ring finger’s task. Instead of supporting the bottom chopstick with the ring finger, Righthand Rule relies on the middle finger instead. This has implications for the manipulation of the top chopstick. The tip segment of the thumb now pulls double duty. It becomes slanted in order to support the top chopstick from both the bottom and from the side, pushing the stick against the index finger.

Righthand Rule is unable to extend tips of chopsticks apart for more than the length of the thumb (below left), compared to Standard Grip (below right). This is a physical limitation that it cannot circumvent. Without the middle finger providing the upward lift past the height of the thumb, as is the case with Standard Grip, it can only pry the top chopstick up using the thumb. Thus the limit.

The middle finger’s duty shifts from the top chopstick to the bottom chopstick. Video clips below highlight ramifications of this one small change. Without three fingers to maneuver the top chopstick, it is hard to leverage principles of the planetary gear train. The index finger and the thumb are still attempting to twirl the stick in Righthand Rule (below left), but they lacks range, precision, dexterity and speed. A proper tripod hold in Standard Grip (below right) unlocks all of these.

Closing salad tongs

Like many alternative grips, Righthand Rule is able to exert considerable power when closing salad tongs. But it does not derive power mainly from the tripod hold as Standard Grip does. Righthand Rule has only a bipod hold. Observe positions of rear ends of chopsticks in the Righthand Rule video (below left), and compare them to those in the Standard Grip video (below right). Note where rear ends rest on the base of the index finger and on the purlicue in both videos. In Righthand rule, the bottom chopstick rests on the base of the index finger. In Standard Grip, the bottom chopstick rests where the purlicue meets the base of the thumb, in what we call a 1-on-2-support.

Righthand Rule is unable to keep the two chopsticks separated without a tripod hold. Thus it resorts to compressing the two sticks between the first two segments of the index finger, against the middle finger knuckle and the base of the index finger. Many alternative grips resort to this strategy as well, even though some shift rear ends of both sticks toward the purlicue instead. These grips include Forsaken Pinky, Idling Thumb, and most grips that derive from Idling Thumb, such as Chicken Claws, Dangling Stick, and Muppet Grip.

Prying open salad tongs

Righthand Rule has almost zero extension power (below left). Again, this is because it lacks proper support from the bottom, for the top chopstick, as demonstrated by Standard Grip (below right). When prodded, a Righthand Rule user may attempt to pry open the two sticks using the thumb on the top chopstick, and the pulp of the middle finger on the bottom chopstick. This effectively turns Righthand Rule into the Turncoat Grip, a grip that sits between Standard Grip and Beetle Mandibles.

This coping strategy is similar to that adopted by users of Forsaken Pinky, when they similarly find themselves unable to pry open salad tongs. A different finger (ring finger) is used (below right), but the concept is the same.

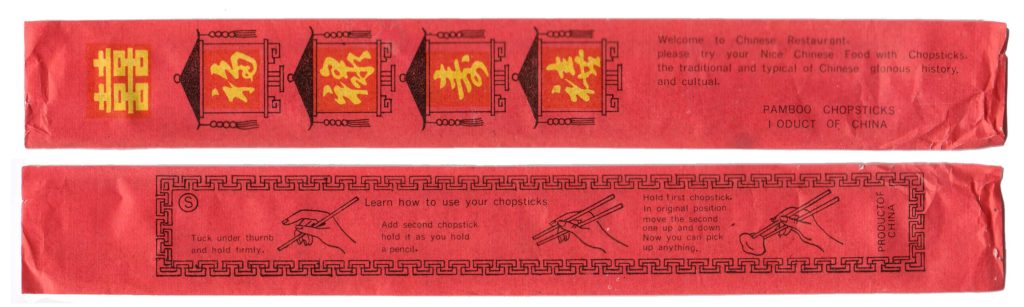

Influence from instructions on wrappers

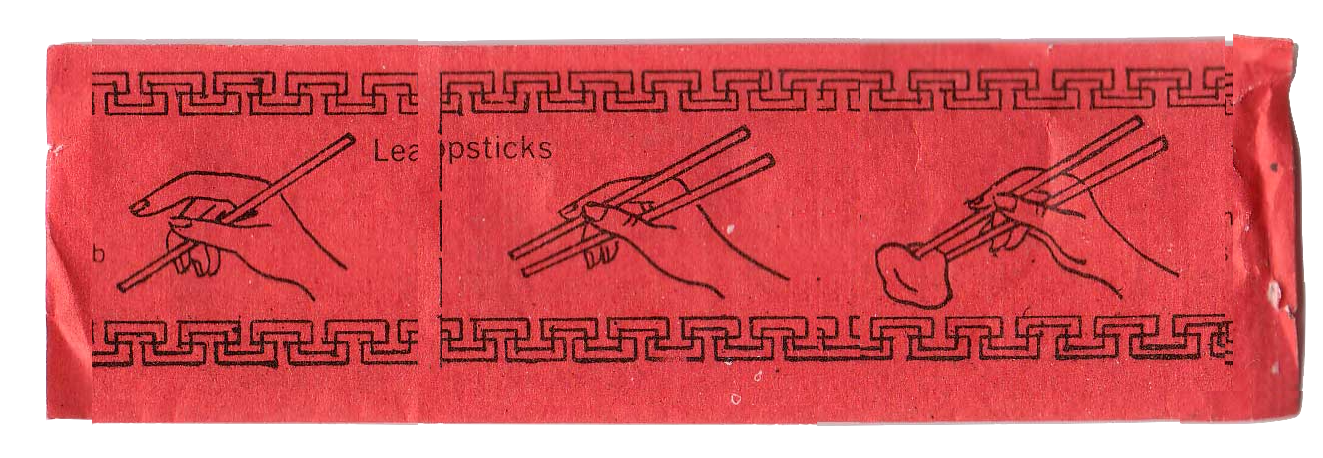

Just like the Vulcan Grip, Righthand Rule is often adopted by adult learners of chopsticks. We think that the ubiquitous “how-to” instructions printed on chopstick wrappers have something to do with the prevalence of this grip among adult learners. Just examine figures shown in the back of the following chopstick wrapper.

We have enlarged the three figures shown in the instruction for clarity. These figures do not show the Standard Grip. They show the Righthand Rule grip instead.

Here we show the last illustration from the wrapper next to a picture of the Righthand Rule grip. They look alike.

That being said, we should note that there is yet another alternative grip which looks not only like the illustration, but is virtually identical to it. That is the Flexed Middle variant (below left) of the Finger Pistol grip.

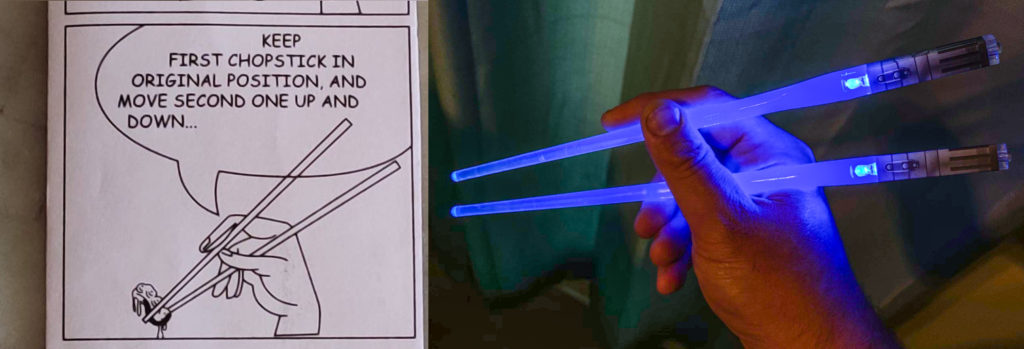

Not all chopstick wrappers come with incorrect instructions or figures. But enough of them do. Here is another wrapper with misleading figures.

The hilarious chopstick video from the Corridor channel on YouTube shows the following chopstick wrapper. It features a person with only 4 fingers holding chopsticks using the Righthand Rule grip. Ironically, the protagonist in the video actually wields the Vulcan Grip.

Righthand Rule in the wild

Plenty of websites show this alternative grip as well. For instance, the Kwik-Stix FAQ page shows a user wielding their ingeniously-modified chopsticks with the Righthand Rule grip.

Below is a short video clip showing Nama Japan picking up thick noodles with Righthand Rule grip. You can see the rest of this video on his Ebisu Ramen Tour.

The “Machines” learning course at Fact Monster is another example. The “Machines” article incorrectly explained the mechanical advantage of chopsticks, as everyone did in the past before marcosticks.org came along. But that is not the point here. Note how Righthand Rule is featured in its illustrations.

Variations of Righthand Rule

A variation of Righthand Rule with a bent thumb is shown below. This variant shares the same “bent thumb” posture as deployed in Count-to-4 and Count-to-kehkuh.

This user uses Standard Grip for picking up light objects, and switches to Righthand Rule, to better hold onto objects. According to the user they are not able to properly apply compression forces with Standard Grip. They find better purchase and dexterity with the Righthand Rule, and with a bent thumb.

In time, we will write an article about this bent-thumb phenomenon. We have observed that may people find Standard Grip and its awkward thumb pose difficult and uncomfortable to wield. We think some people have anatomical differences that make it nearly impossible for them to ever adopt Standard Grip.

Connections to the Lateral grip family

The largest chopstick grip family has a special connection to Righthand Rule. This grip family is the Lateral chopstick grips. The family includes classic swing variants such as Lateral Chick, Lateral Squid, and Lateral Gangnam Style. There are also variants sporting sideway swing and underswing. Then there are hybrids such as Lateral Turncoat.

All Lateral grips share one common trait. That is, their Compression posture closely resembles Righthand Rule. The picture below left shows a typical Compression posture of a Lateral grip. Note how similar it is to the Righthand Rule picture, shown below right.

But there is a key difference between Lateral and Righthand Rule. Note how the first segment of the thumb in Lateral Turncoat shown above left does not touch either chopsticks at all. Only the thumb base is used on Lateral grips. In contrast, the pad of the thumb firmly operates the top chopstick in Righthand Rule shown above right. Lateral grips differ from Righthand Rule, mainly on its disuse of the tip segment of the thumb. This disuse of the thumb makes Lateral grips operate with completely different finger dynamics.

Learn more grips

Users of Righthand Rule can easily add Standard grip to their chopsticking repertoire, by raising distal knuckles of the middle finger and the ring finger. Doing so allows the middle finger to participate in the tripod hold on the top chopstick, and the ringer finger to help with the 1-on-2-support for the bottom chopstick. Learn to twirl chopsticks, if you are interested.

Taiwanese: 正手定律

This grip is known as 正手定律 (Chiàⁿ-chhiú tēng-lu̍t) in Taiwanese. It may also be known as 正手法則 (Chiàⁿ-chhiú hoat-chè).