Last Updated on June 15, 2021 by Staff

Many chopstick users wield authentically-looking Standard Grip, and are able to pick up food items at most eating situations with perfectly-executed alternating motion. However, a large percentage of these users are unable to exert much extension force using their chopsticks. We have named this phenomenon the Weak Standard Grip.

Table of Contents

Snapping at the thin air

The standard grip finger posture and dynamics can be learned fairly quickly, if the right principles are taught. Many users are able to then wield chopsticks with finger posture and dynamics that look almost indistinguishable from the standard grip. Often this is demonstrated by having a user snap at the air with chopsticks. We post pictures and videos of such air snapping on this site all the time.

The salad tongs test

But snapping at the air does not really require much compression or extension force. In most eating situations, only a moderate compression force is required. Occasionally, one will need to pick up a heavy item, or pry open a food item. That is when the weak standard grip reveals itself.

We have been conducting salad tongs-based tests lately. Recent articles all feature video clips of users attempting to open and close salad tongs. We especially like the test where a user needs to pry open a pair of salad tongs bound by a rubber band. This difficult task has become our litmus test – it reveals any weakness in a user’s mastering of the twirling of chopsticks. Using this litmus test, we have been able to identify several causes of the weak standard grip.

Authentically-looking grip

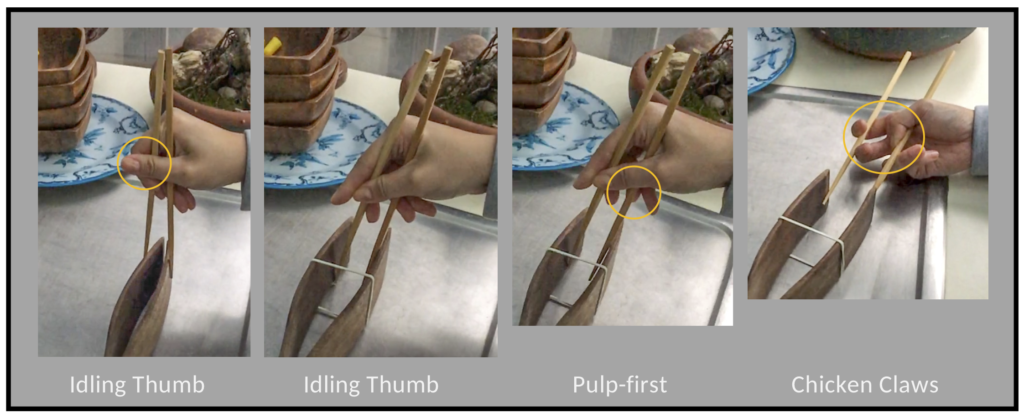

But first let’s look at pictures of two more users snapping at the air using the weak standard grip. These too can pass as textbook examples of how to wield chopsticks.

Unlike the “pseudo” standard grip we’ve termed Idling Thumb Grip, this grip is indistinguishable from the standard grip, given only the above pictures. In fact, videos clips of users snapping at the air also look completely correct. The planetary gear actions are clearly visible.

Closing salad tongs

Under the salad tongs tests, however, small differences in finger dynamics start to become discernible. The clip below on the left is a slow-motion capture of a user closing salad tongs, with a weak standard grip. Pay attention to the top chopstick in the beginning. The stick slips. Compare this clip to the (stronger) standard grip video on the right. The reason for the slippage is that the top chopstick is no longer securely caged in from three sides by three fingers, tripod-fashion.

The user on the left isn’t consciously maintaining a finger configuration based on the planetary gear train. Thus, the thumb slips, and the rest is history. The user on the right extends and flexes the tip segment of the thumb, in response to opposing forces presented by salad tongs. This keeps the top chopstick properly surrounded by the three fingers, throughout the alternating motion.

This issue is elucidated by comparing the thumb slip (left) to the equivalent test from Idling Thumb Grip (right). Under stress, users of these two grips end up with similar-looking finger motions.

Prying open salad tongs

The fact that the thumb is neglected by the user becomes undisputed, when the the test switches to having the user pry open salad tongs bound by a rubber band. Refer to clips shown below. Note how all standard grip guidelines have been thrown out of the window. The finger motions (left) have become identical to that of a Idling Thumb user (right).

Note the lapse of proper finger motions in this weak form of standard grip, shown in the clip below to the left. Compare it to the (stronger) Standard Grip equivalent shown below to the right. The user on the left has abandoned the tripod hold on the top chopstick. The user on the right continues to maintain a good tripod hold throughout the alternating motion.

Turning into Vulcan Grip

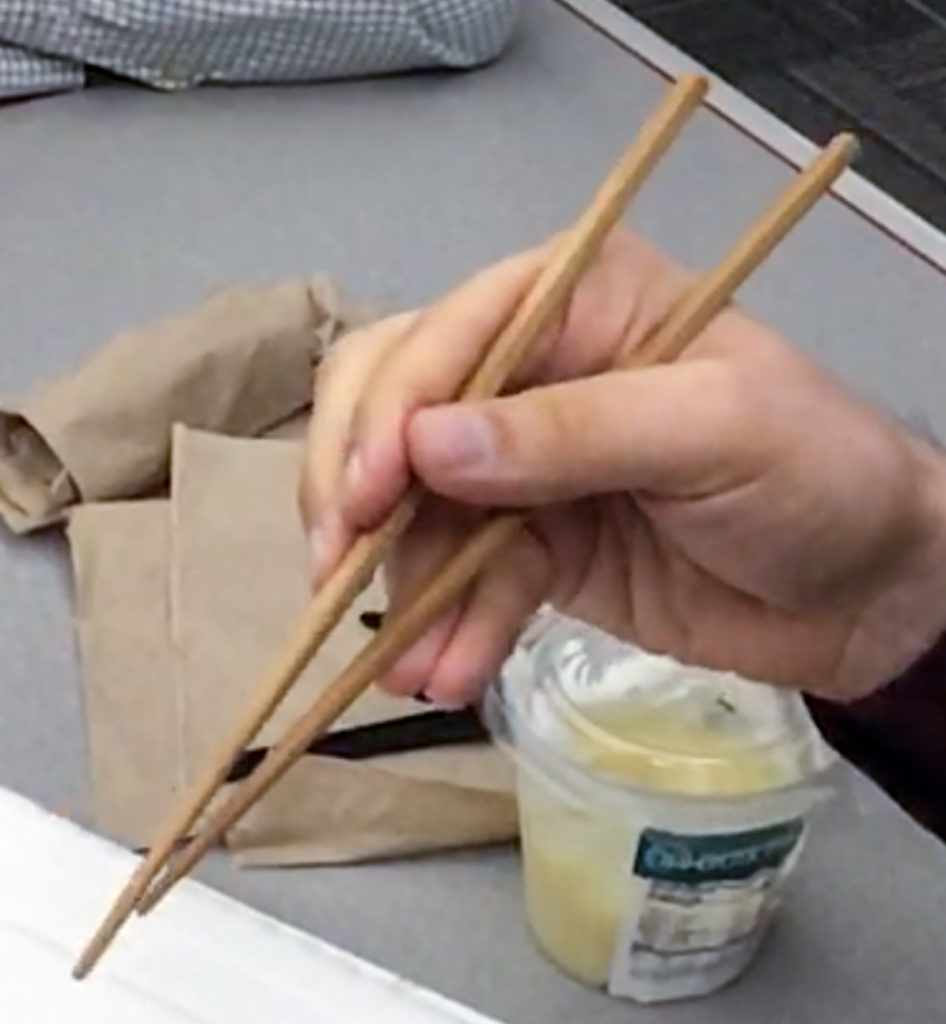

In an attempt to generate a significant extension force, some users turn to Vulcan Grip for inspiration. In the left clip below, the user changes the role of the ring finger. Instead of supporting the bottom chopstick with its distal knuckle, the ring finger now uses its pulp area to try to push the bottom chopstick away. Compare the left clip to the Vulcan Grip picture to the right.

Turning into Chicken Claws

Sometimes this struggle makes a user turn to Chicken Claws Grip for inspirations. Note what happens in the clip below to the left. Compare it to the equivalent test with the Chicken Claws grip on the right. This is an outright abandonment of the tripod hold duty of the thumb, with respect to the top chopstick.

Coping with duress

The following illustration summarizes the three different ways with which a user attempts to cope with stressful situations requiring a large compression or extension force.

We have now discussed three grips that derive from Standard Grip, all involving a neglected thumb tip, to one extent or another. In the order from the the closest to the most distant in relatedness, they are: Weak Standard Grip (the present topic), Idling Thumb Grip, and Chicken Claws Grip.

But technically the Weak Standard grip is not an alternative grip, unlike Idling Thumb and Chicken Claws. Its users do already practice the right Standard Grip finger postures and alternating motion. The weakness stems from a lapse in upholding key principles of Standard Grip, in stressful situations.

Negligence of the 1-on-2-support

The lapse in engaging the thumb tip in twirling the top chopstick is not the only cause for a weak standard grip. There are other ways to weaken the standard grip. The following slow-motion clip shows a different user who can generate enough compression force, to confidently close salad tongs. The tip segment of the thumb properly engages the index finger and the middle finger to twirl the top chopstick. However, as we will see later, opening chopsticks under stress is a different matter.

The following video clip on the left is a slow motion capture of the same user prying open salad tongs. Note how the user starts out with the standard grip finger configuration, for the bottom chopstick. But very little extension strength is generated, because the thumb and the ring finger have temporarily forgotten how to securely hold the bottom chopstick in place, using the 1-on-2-point-support principles. As an alternative, the user reconfigures the ring finger to adopt the Vulcan Grip instead, in a successful attempt to gain purchase. Compare the left clip to the Vulcan Grip picture to the right. This gain comes at great costs – see the Vulcan Grip article for details.

Learn new grips

Users of a weak standard grip can adopt the (stronger) standard grip by first identifying their weaknesses via the salad tongs test. If the root cause is a neglect of the thumb, then simply learn to better make use of the tip segment of the thumb, and to maintain a tripod hold on the top chopstick throughout the alternating motion. If the root cause is a neglect of the 3-point-support for the bottom chopstick, then practice snatching the bottom chopstick until the bottom chopstick can no longer be snatched away. Learn to twirl chopsticks, if you are interested.

Taiwanese: 無力標準法

This grip is known as 無力標準法 (bô-la̍t piau-chún hoat) in Taiwanese.