Last Updated on January 30, 2022 by Staff

This article is a retrospective on two years of research into chopsticking. What started as a prank website has become a serious inquiry into the art and science of wielding two sticks in a hand. Marcosticks.org now bears witness to our ever-expanding knowledge of how chopsticks work, and why they work. It is the right time to look back, and reflect on what it all means, to us.

We started the journey as self-righteous chopstick traditionalists. We looked to explain why “the one right chopstick grip” was the only way to use chopsticks. We would then make everyone else who wielded “the wrong grip” repent, and reform. But our research ended up leading us to a completely different perspective on chopsticking. We have now turned 180° around.

#GripEquality

Table of Contents

Prejudice vs reality

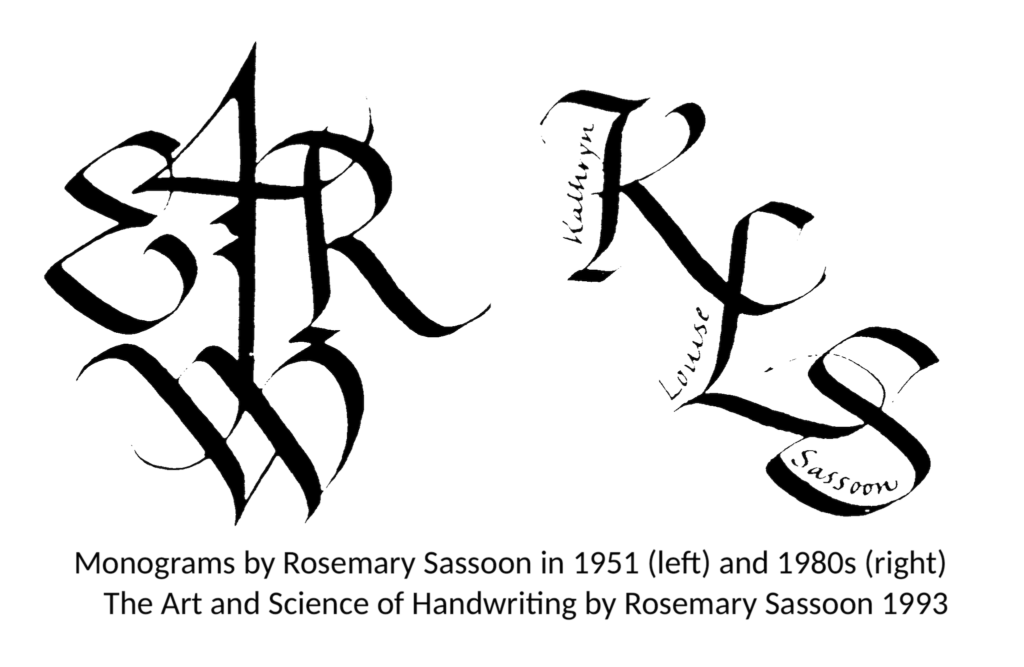

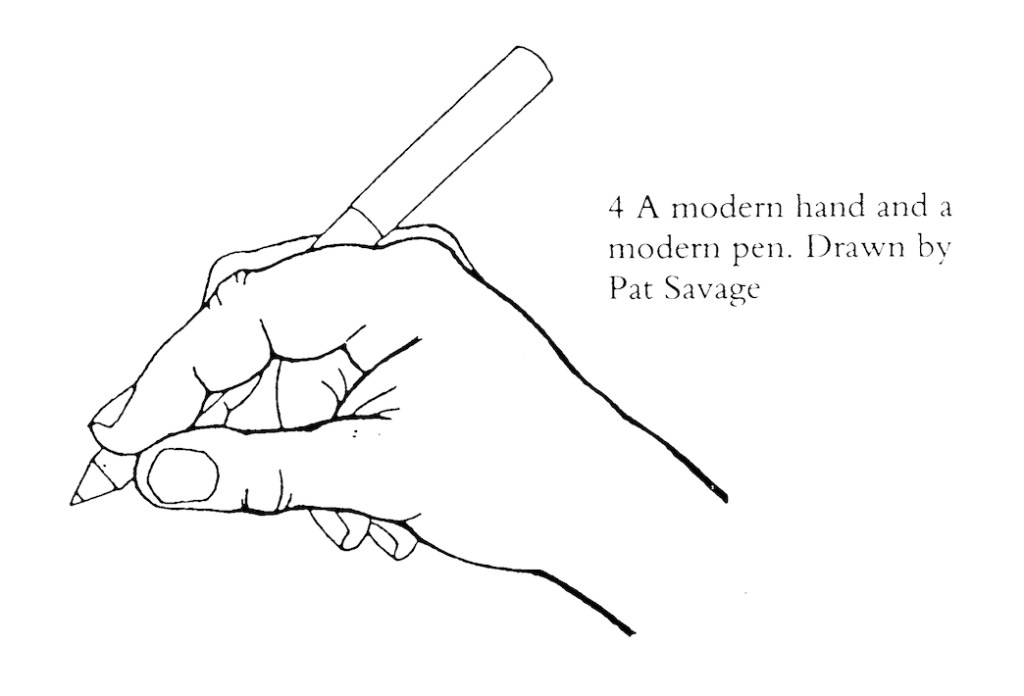

We regret not having discovered sooner Dr. Rosemary Sassoon, her lifelong work, and especially her 1993 book, The Art and Science of Handwriting. She shows us that the pursuit of science and the perfection of art do not need to come at the expense of humanity.

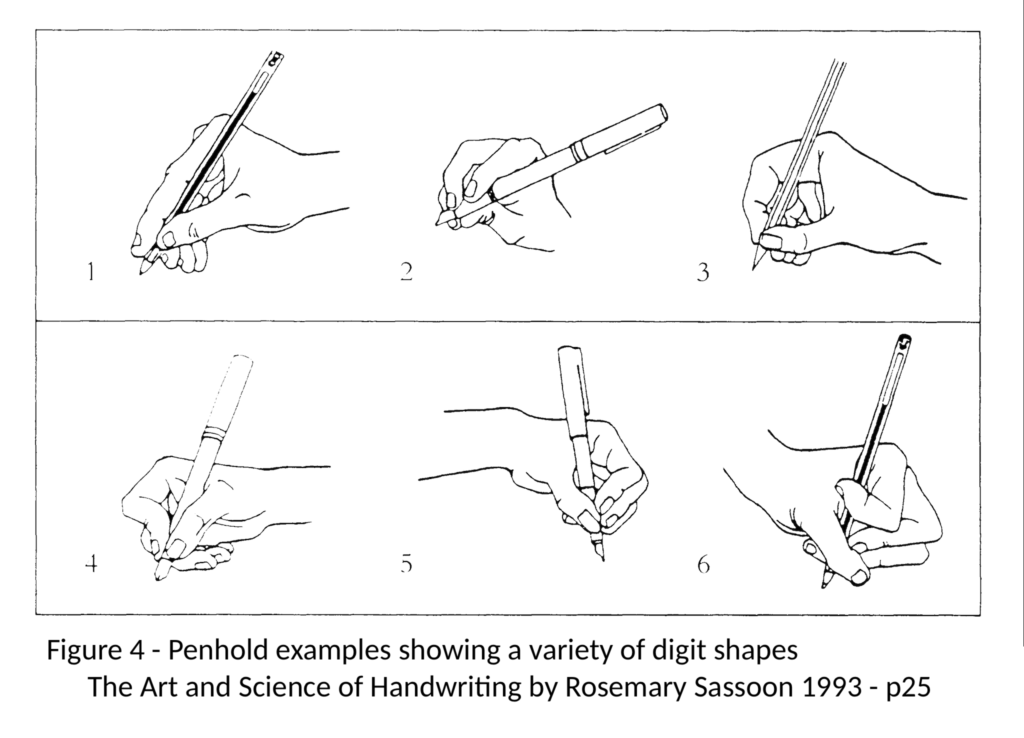

While Dr. Sassoon hacked away at secrets of penholds and the resulting handwriting, we tried to unveil finger dynamics behind multitude of chopstick grips. We wanted to compare them by their relative power, dexterity, reach, speed and finesse. Dr. Sassoon and we both pushed to uncover cold hard facts about penholds (or chopstick grips in our case), be them conventional or nonconventional grips.

But after spending the first significant part of her life perfecting the precise and draconian art of handwriting, and then another significant part on the science of proper penholds, Dr. Sassoon discarded her prejudice, as all good scientists do, when faced with mounting evidence she herself helped to uncover, to the contrary.

And we humbly and belatedly arrived at the same conclusion that she already articulated in 1993. That is, our research is not a race to eliminate unconventional grips. Our quest is not to crown one correct grip for all to wield.

Instead, we want to understand why people adopt wildly different grips in the first place. We must identify hidden causes driving people to use these grips. Only then can we assemble a menu of grip options, with objective assessments of their relative merits, such that any individual can find a grip that works best, for their particular circumstances and personal needs.

I began to doubt whether statistical evidence was either possible or desirable in many areas of handwriting… it is the variability of the findings that are important in that they point to the need to consider the writer as well as the reader.

Dr. Rosemary Sassoon 1993

Being ridiculed for using the wrong chopstick grip

Most people from chopstick-using cultures can relate to the common experience of someone being ridiculed, for using chopsticks the wrong way. Almost always, the accuser is unable to articulate why the wrong way is wrong, except that it is “not correct”. Often the accuser himself wields a grip that someone else would deem incorrect.

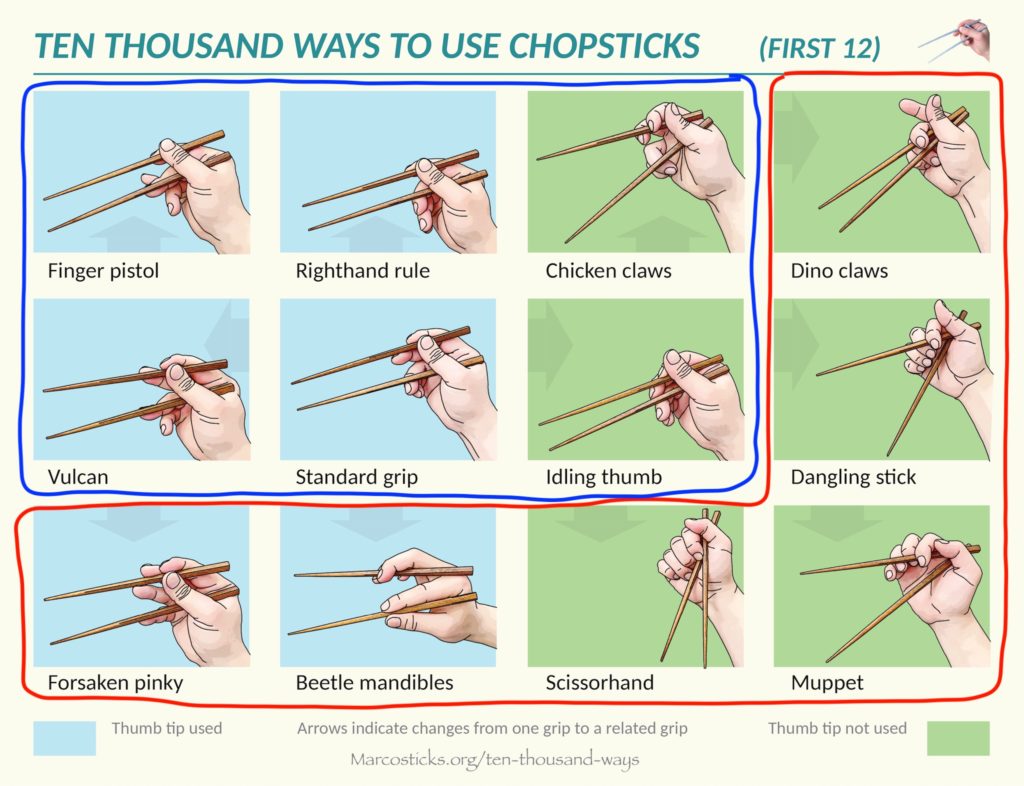

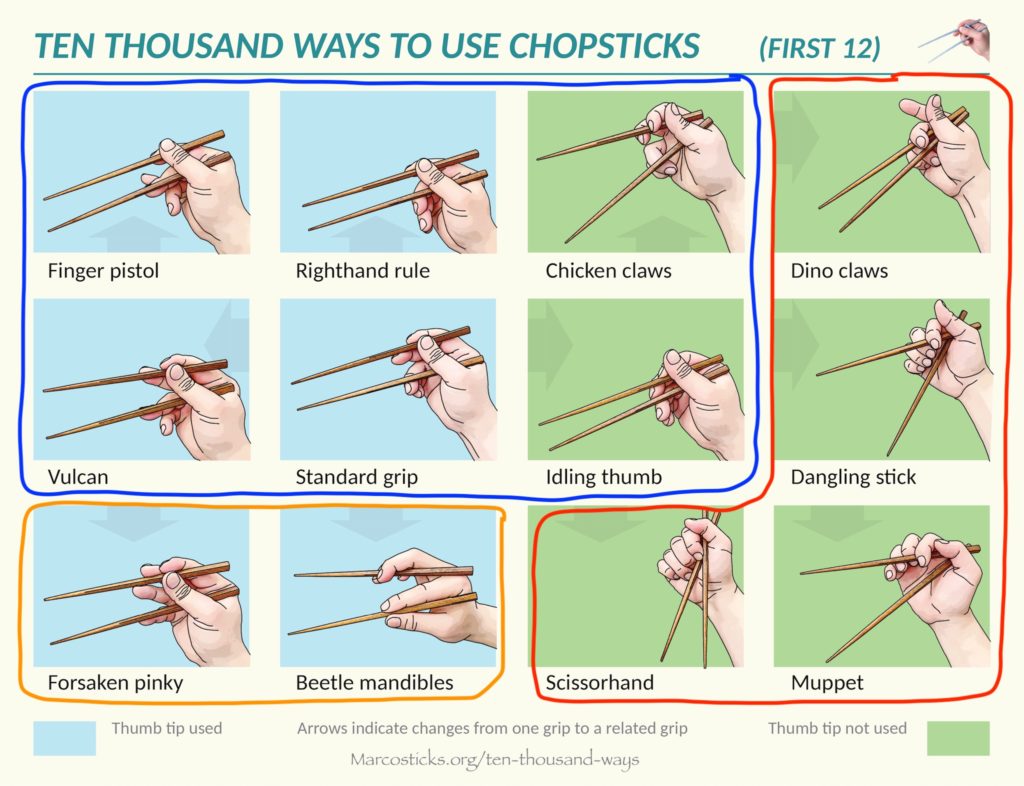

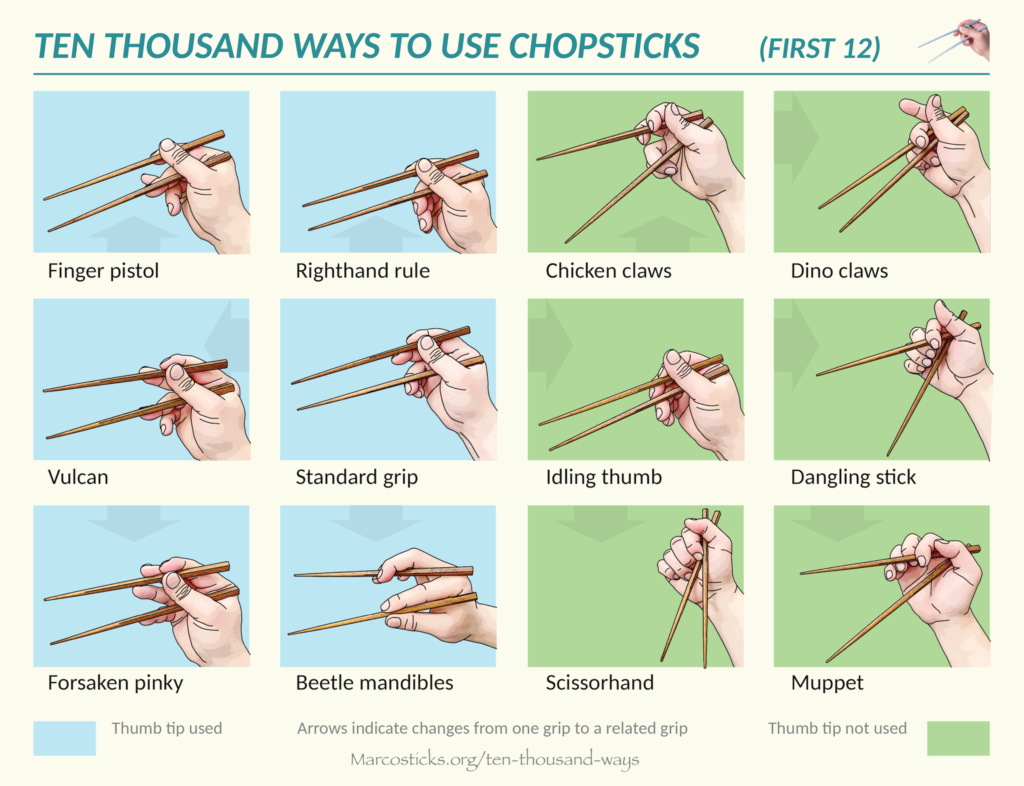

Our research found that there are at least 30 ways people hold chopsticks. We’ve published analysis of 18 of these chopstick grips, at the time of this reflection. The first 12 of these grips are shown below. Most people will consider the 6 grips circled in blue, “the correct way”, while the 6 grips circled in red are generally considered “wrong”.

If pressed to explain why the wrong grips are wrong, most will point to the picture shown below, and say something nebulous like, “the 4 grips circled in red are crossed”. Or they may say, “the 4 grips circled in red move the bottom chopstick – that’s wrong”. Most people will simply say that the 2 grips circled in orange look “odd”.

The need for classification of grips

There is one root cause for this confusion. That is, no one bothered to study grips, identify distinct grips, name them, and classify them into a family tree based on features and relatedness. So we did.

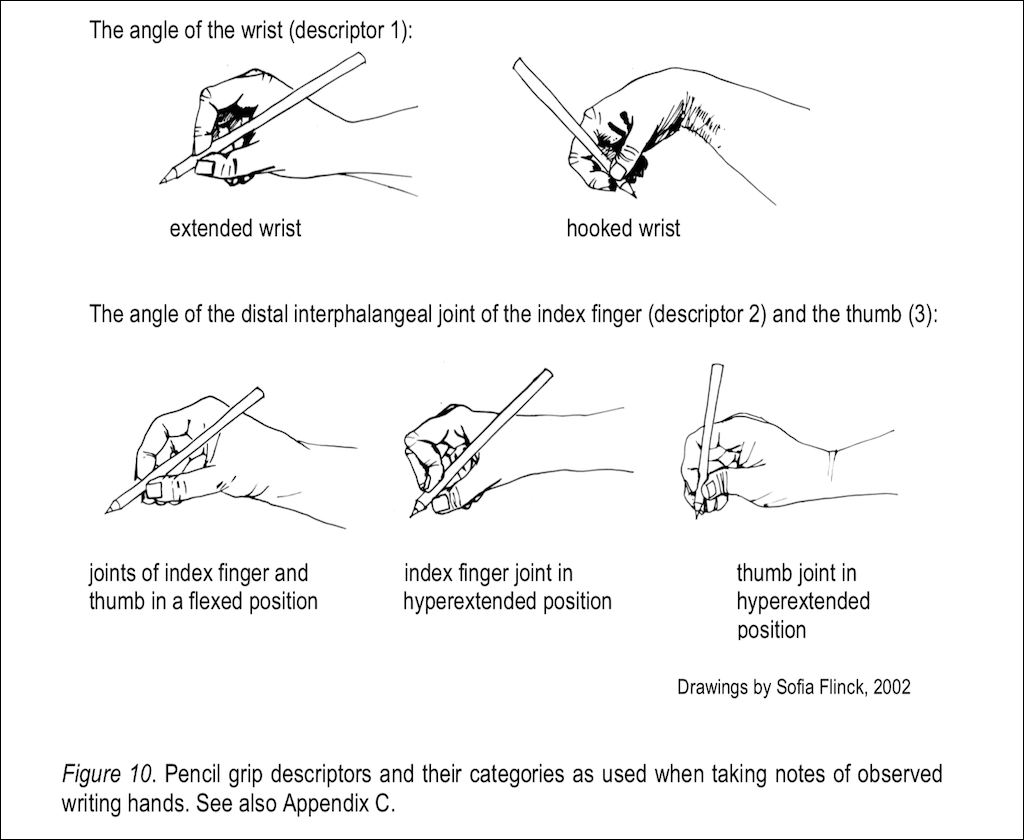

The picture above-left identifies chopstick grips descending from Idling Thumb. Similarly, Sassoon 1993 analyzed penholds, and classified them based on features. The illustration above-right describes variations of digit shapes given one penhold posture.

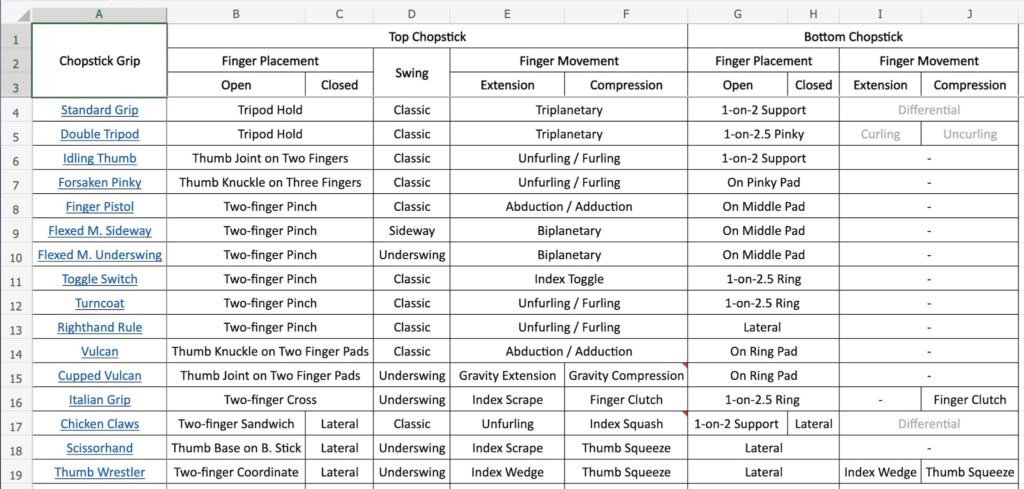

Our research unambiguously showed that every one of the dozens of grips we named and classified is unique. Each has its own finger dynamics driven by its own biomechanical advantages. When measured by objective metrics such as power, dexterity, reach and speed, each grip has its own distinct profile. The above chart of grips is interactive. Click on any picture to learn about what we know of this chopstick grip. You can find more related, interactive guides at: (clickable catalogs) 19 Common Chopstick Grips. Also visit: Ten thousand ways to use chopsticks.

Now, we can refer to distinct grips by name. We can compare grips, and discuss their relative merits. Often we would isolate features or factors of chopsticking, and compare grips based on a single factor, at a time.

For instance, we can bucketize all grips into exactly two groups, if we consider only one factor – whether the thumb pad is used to move the top chopstick. Then we can analyze relative merits of the two groups as wholes.

The art of chopsticking

Evaluating grips by distinct factors thus allows us to isolate and identify effects of each factor on chopstick grips. The following diagram divides 12 common grips into thumb-pad-using (left, blue), and thumb-pad-unused (right, green). It is immediately clear from just this picture that blue grips have rear ends of chopsticks separated far, while green grips have them stuck together.

One practical consequence of keeping rear ends together is the need to “clutch” the hand into a fist, in order to close tips of chopsticks. This is demonstrated drastically in Dino Claws, Dangling Stick, Muppet, and Scissorhand. And the all member grips in the large Lateral grips family share the same clutching of chopsticks. It is less prominent in Chicken Claws and Idling Thumb, but still noticeable enough, when one knows what to look for.

This thumb pad observation invites hypotheses that can be tested systematically by well-designed experiments. For instance, we hypothesize that early exposure to chopsticks in chopstick-using countries forces preschoolers to acquire green grips. Young kids find ways to clutch two long and heavy sticks, resulting in their adoption of green grips even past childhood. In contrast, adult learners in Western countries more often adopt blue grips.

What else? Well, we can chuck that visual “crossness” classification out of the window. Some of those crossed sticks are artifacts of users holding chopsticks midway, such as in Muppet. Crossed sticks have nothing to do with actual operations of Muppet. On the other hand, some crossed sticks are essential to the function of a chopstick grip, as we describe in Scissorhand and Cupped Vulcan.

Instead of crossedness, we study whether the top chopstick swings under the bottom chopstick, based on scissor-like mechanisms, as is the case with Scissorhand, but not Dangling Stick. Further examination reveals that theoretically, most grip types have three closely associated variants: classic swing, under swing, and sideway swing. These are better descriptors for grips, than the nebulous, visual “crossedness”.

We now know that some grips such as Dangling Stick, Muppet and Cupped Vulcan call for gravity assist in their operations. These grips would not work well for astronauts, in the International Space Station.

We can observe practical consequences resulting from relative merits of these grips. We can measure metrics such as compression power, extension power, reach, precision, dexterity, and speed.

Chopstick users learn to make up for shortcomings in their chopstick grips. By trial and error, they soon master a grip despite its imperfect metric profile. For instance, a user masters Cupped Vulcan by leveraging gravity to make up for its inability to extend tips of chopsticks apart. Despite an imperfect grip, finesse results.

We call this the art of chopsticking.

The so-called traditional way

We wrote earlier that most people don’t think of the six grips circled in blue as different. To most chopstick users, they are the same “correct” chopstick grip.

Yet, most chopstick instructions from newspaper articles and from YouTube videos are unanimous in describing only one grip out of these six. This is also true when it comes to crude instructions printed on chopstick wrappers. Their written words unambiguously describe this one grip, even if illustrations on wrappers are often wrong.

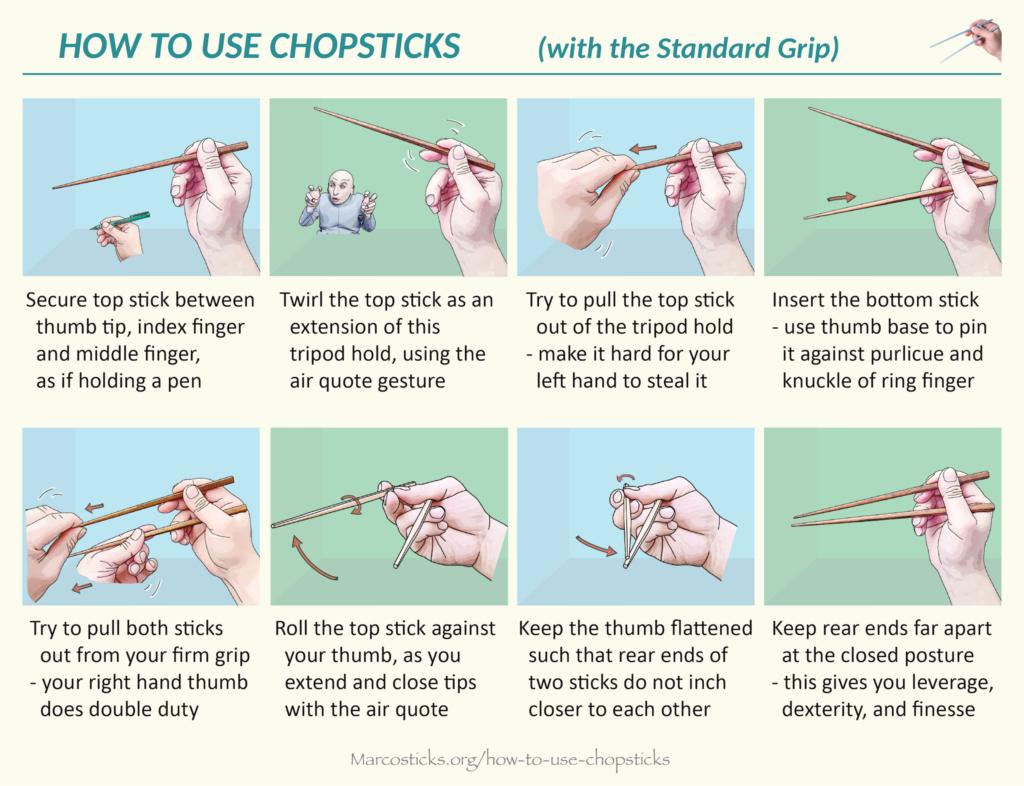

They all describe what we call the Standard Grip.

So, the general populace only has a vague idea of what is a good grip. They’ll treat anything looking like Standard Grip as the correct grip. But the small group of people writing instructions and making instructional videos do know better. They at least can write down in words, that the thumb, the index finger and the middle finger operate the top chopsticks. They also write that the base of the thumb holds the bottom chopstick immobile against the ring finger and the purlicue.

But that is where these instructions end.

Instructions in the past do not talk about how fingers actually move the top chopstick. No one writes about how the three fingers hold the top chopstick, and dance in synchrony to wield it with power and reach. Standard Grip requires an unnatural thumb pose, but a significant population is unable to sustain this weird thumb pose. Lastly, the bottom chopstick can actually be moved. It can be dexterous, too. That is a secret no one has documented before.

Form vs. function

Why is Standard Grip the favorite for people who write chopstick instructions? Most can’t answer this question. Certainly we know of no video instructions nor written instructions from other people that elucidate this point.

Many people, however, subscribe to the notion that the traditional grip is aesthetically beautiful. And that wrong grips are odd and ugly.

We no longer think such view holds water. Look at pictures below, showing Standard Grip on the left, and Cupped Vulcan on the right. By what criteria is it judged that Standard Grip is more aesthetically pleasing than Cupped Vulcan? Who makes the call? And where is it written?

Here is yet another example. Most chopstick users can’t tell the (plain) Vulcan grip from Standard Grip. It is regarded by most as “the traditional grip”. Following pictures show Vulcan on the left, and Muppet on the right. By what criteria is it judged that Vulcan is more aesthetically pleasing than Muppet?

We think function should trump form, when it comes to chopsticking. Our research shows that Standard Grip is objectively the most efficient chopstick grip in terms of function, overall.

But it is not the best in all metrics we measured. For instance, Equal Opportunity extends chopsticks further apart and far easier than Standard Grip can.

Objectively speaking, Standard Grip is our favorite because it presents a balanced profile, when all metrics are considered. These metrics include compression power, extension power, reach, precision, dexterity, and speed.

We are not the first to describe some of these metrics. But we are the first to do so with 18 grips, instead of the simplistic classification of grips: correct vs incorrect. We also emphasize extension power and chopstick reach. Because finesse comes as a balance of compression vs extension power. And precision is ironically a result of being able to command an expansive chopstick reach. * note1

While analyzing and writing about various chopstick grips, we compare them against one another. But unavoidably, we always end up using Standard Grip as the benchmark, in our analysis of every alternative grip.

Chopsticks as glued-on extensions of fingers

After analyzing 18 grips and comparing them to one another as well as to Standard Grip, we can confidently declare Standard Grip the first choice for anyone learning to use chopsticks. This assumes that a learner is physically able to wield this grip without anatomical constraints. More on anatomical constraints later.

Standard Grip is our favorite, because it allows fingers to affix the two chopsticks to themselves, turning these sticks into exoskeleton-like extensions. Standard Grip delivers excellent power, reach, precision and dexterity, chiefly because the two sticks become figuratively glued onto fingers. To a bystander, these two chopsticks indeed look like glued-on extensions of a user’s fingers.

Most alternative grips lag behind in this crucial aspect.

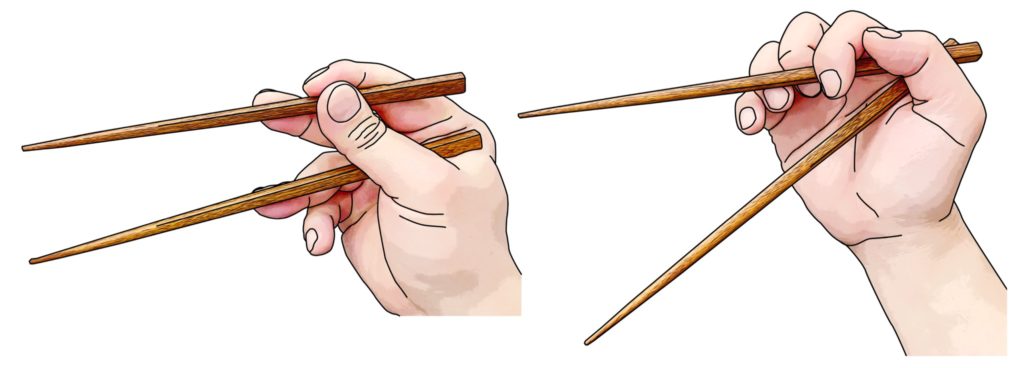

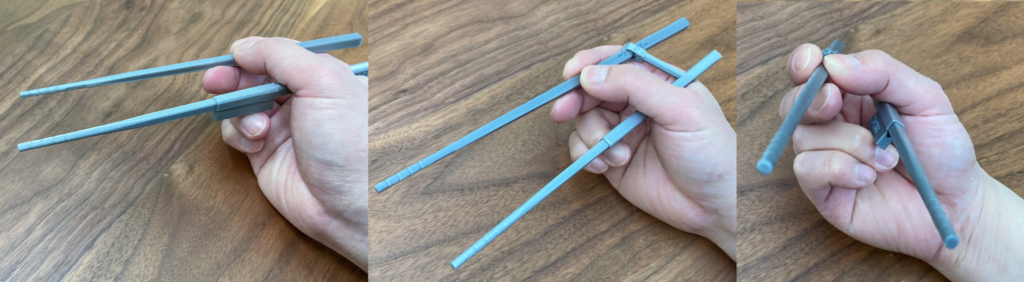

Assessing whether a grip can turn two chopsticks into secure extensions of fingers is a complicated process. Often one needs to carefully study slow motion captures of the grip in use, when physical tests cannot be conducted. However, there is a quick visual confirmation that anyone can perform, as an approximation. Simply compare the closed posture of a grip to its maximally-open posture, as shown below for Standard Grip.

Note how the thumb pad, the index finger, and the middle finger secure the top chopstick, in both ends of the chopstick motion. Their positions remain virtually unchanged. Note how the top chopstick is virtually glued onto both the index finger and the middle finger, for the entire length of these two fingers.

Look at the bottom chopstick. It may appear to have shifted during the motion. But it has not. Where it contacts the knuckle of the the ring finger has not changed. Where it contacts the purlicue remains the same.

All that has happened in the transition from the picture on the left, to the picture on the right, is that these fingers “rolled” both chopsticks against finger skin. They do this rolling without ever losing firm contact with chopstick surface. This is detailed in our article on planetary gears.

The same cannot be said of most alternative grips. Some grips have drastically different finger configurations for the closed end, and for the open end of the chopstick motion. Chicken Claws is one sample.

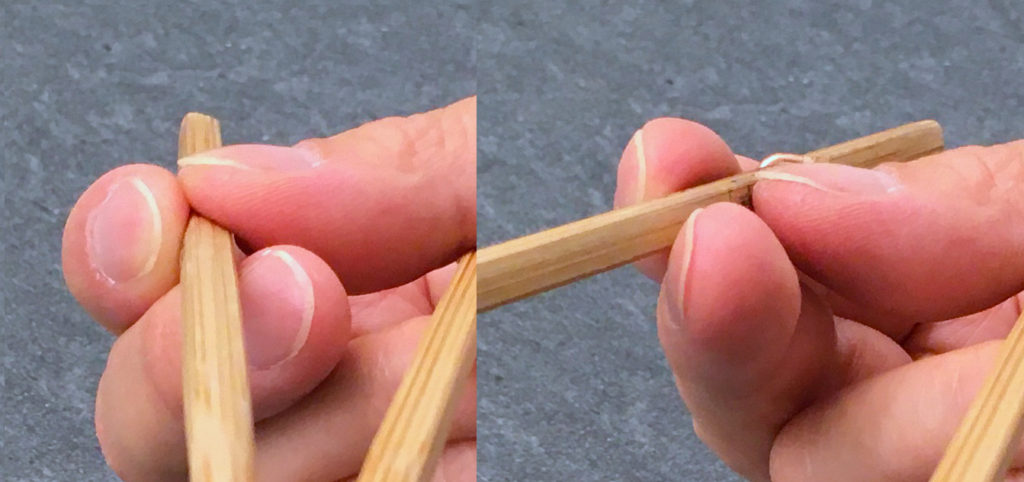

Some grips have the same visual finger configurations in the two ends of the chopstick motion. But in one end of the motion, the fingers are weak, and either find no firm purchase on a chopstick, or cannot exert enough force to nudge it. Take Righthand Rule as an example. Recall that most chopstick users think of this grip as a traditional grip. Based solely on observations of two pictures shown below, it does appear that this grip can close and open chopsticks.

We regularly conduct what we call the “salad tong extension test”. This test is feared among our test group. It requires that a user pry open salad tongs, by extending tips of chopsticks apart.

When we examine actual operations of Righthand Rule with this litmus test, we discover that the top chopstick is not at all attached to the fingers. The video below to the left shows that Righthand Rule has virtually no extension power. The user has to switch momentarily to the Turncoat grip, to try to get a better purchase. This is accomplished by the ring finger relieving the thumb base of its bottom stick duties, so the thumb can be reconfigured to push upward on the top stick.

Regardless of which alternative grip someone adopts, when push comes to shove, everyone can always pull out the trump card called “clutch chopsticks in your hand”, to close salad tongs. But no equivalent trump card exists for the extension test.

A modern take on how-to instructions

Armed with new insights from these grip investigations, we think it is time we rewrote how-to instructions for chopsticking. We think that in time, all chopstick grips should have their own instruction sheets written.

But let’s start with Standard Grip first. Here is a version that we think captures all crucial, new insights. These are presented in the briefest fashion we can manage, with detailed illustrations. Feel free to share the full-resolution instruction image everywhere online.

The instruction sheet does not attempt to explain why any step is prescribed. There isn’t enough space in this simple instruction sheet for that. But all of these steps are discussed in details on marcosticks.org. You will find some articles helpful in understanding our modern how-to guide, listed below roughly in the order the panels are read:

- Hold Chopsticks like a Pen

- Air quotes: Planetary gears and chopsticking

- Chopsticks as extensions of fingers: Learn to Use Chopsticks

- Flattened thumb: Caswellian thumb and chopsticks

- And of course, the Standard Grip article itself

A summary of these articles can be found in the video version of the how-to guide, shown above.

The science of chopsticking

Very little research has been done or published on the science of chopsticking. There are, for sure, papers on chopstick grips, as we reported in History of Chopstick Research. But most of these do not even distinguish grips from the two crude groups we mentioned at the beginning of this article: correct vs crossed. Speed and range were measured. But more often than not, conclusions were inconclusive, because nobody could make sense of collected data.

That shouldn’t surprise readers who have read so far. When those six traditional-looking grips were lumped into one single group, we should instead be surprised, if anyone did draw any defensible conclusions from data.

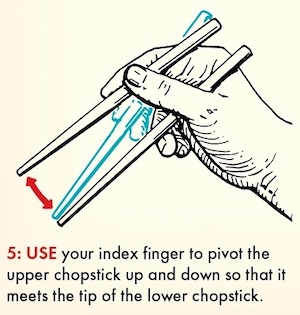

Besides, chopsticks research still lingers at the chopstick-as-Archimedean-lever stage of misunderstanding. Researchers treat chopsticks as third-class levers with fixed fulcrums. That is not how chopsticks work. Most chopstick grips we analyzed do not work that way. Certainly Standard Grip does not. This misconception is perpetuated in text books, and in famous how-to-use-chopsticks guides, such as the How to Use Chopsticks Like Mr. Miyagi which goes viral every so often on social media such as Reddit.

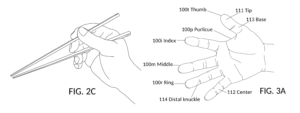

We broke the news that Standard Grip operated on the principle of planetary gears. It is weird that no one in thousands of years had made this simple observation. That article was written in December 2019, after we filed two patent applications disclosing this finding, plus training chopsticks designed based on this insight. Here is the first patent application on ergonomic chopsticks. * note3

In the next video, we keep the camera trained on the top chopstick, so that it appears immobile. Instead, the bottom chopstick and the rest of the hand appear to tilt away from it. This allows you to observe the rolling of the top chopstick by the three fingers (aka planet gears), without distractions. Note how the top chopstick is “rolled” by the three fingers.

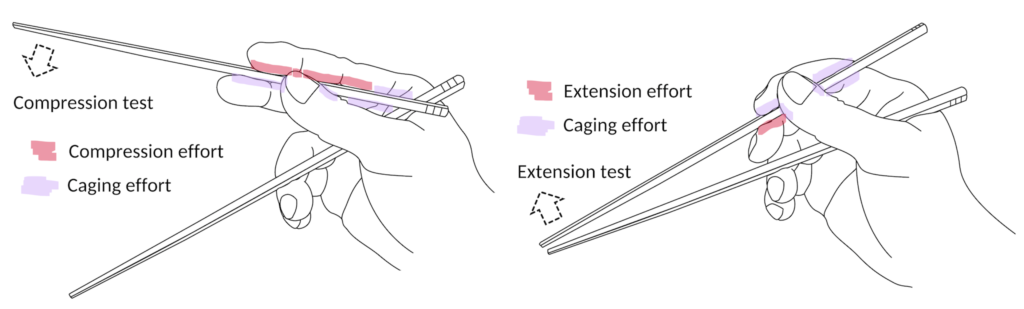

As it turns out, this planetary gear rolling of the top chopstick enables the hand to securely grasp the top chopstick as an extension of fingers. It allows an entire finger to exert forces on the stick, not just at one Archimedean “effort point”, but on a large area of chopstick surface. There is not a single fulcrum. But instead, an entire finger surface from another finger serves as counter force to securely cage and sandwich the chopstick, turning it into a cantilever extension of fingers. Standard Grip is one of the few chopstick grips where the same sandwiching principle works for both compression and extension.

At this point, we believe we understand the basics of the science behind Standard Grip. We should apply the same investigation into every grip we have written about, beyond rudimentary observations and comparisons we have written so far.

Science is celebrated for its prediction power. Earlier we talked about classifying grips based on how the top chopstick swings. We theorized early on that all major chopstick grips that swung the top chopstick upward (i.e. classic swing) had theoretical counterparts, with either a sideway swing, or an underswing. In time, we have discovered such sideway swing and underswing variants of grips we previously analyzed. The Lateral grip family is the best example that confirms this theory. * note2

Anatomical differences in human hands

We were given hints about anatomical differences in human hands very early on. The ergonomic marcostick prototypes we created did not work on a few individuals in our test group. We noted that one person in particular could not make the thumb pose required for Standard Grip. Forced adoption of Standard Grip for this user led to chopstick cramps. We created the model T training marcosticks and model H finger helpers in response, but did not think much further about this thumb condition.

It wasn’t until after folks sent us more pictures and videos of their alternative grips, that we started to appreciate this as a prevalent issue. Some people appear not to be able to wield this thumb pose which we have termed the Caswellian thumb pose. Some report hand cramps when forced to make this pose for extended periods of time. Many alternative grips such as Count-to-4 and Equal Opportunity appear to have been independently invented by folks trying to cope with anatomical differences.

Our foray into the relationship between penholds and chopstick grips brought us eventually to Dr. Selin’s 2003 work and Dr. Sassoon’s 1993 work. We can definitely say now, that the Caswellian thumb pose is not a universal trait. Modern penholds largely abandoned such flattened thumb pose, in favor of variants of dynamic tripod where the thumb IP joint is flexed (bent). In 1993, very few students were observed to wield a Caswellian thumb pose. Even fewer were recorded in 2003 (less than 1%).

This insight led us to read up on medical literature. It turns out that the human hand is not all built the same way. There is a substantial variation in how muscles, joints and nerves are built and connected. Dozens of muscles coordinate, to move fingers. In some people, these muscles originate from different parts of bones. In others, these muscles and their tendons are inserted into different finger bones. Innervation can be very different between individuals. Lastly, some of these muscles are missing altogether, in large percentage of people.

Perhaps Caswellian thumb is not the only manifestation of this variation in hand builds. We already know that a sizable population has hitchhiker’s thumb. It is possible that some chopstick grips were independently invented by folks whose hand builds can best utilize them. We won’t know for sure, until we dig deeper, into every single alternative grip, and canvass much larger population of chopstick users.

Our first post on Reddit generated a thousand comments in December 2020. Many talked about cramping of the hand while using chopsticks. Dr. Sassoon’s work on penhold made us see these comments in a new light. Consider these two pictures shown below.

Callewaert’s penhold, shown above left, is one alternative penhold that Dr. Sassoon recommends to her patients who suffer from writer’s cramp. For some people, this may provide temporary, and even permanent relief from cramping. We have also published an alternative chopstick grip which adopts the same finger dynamics, shown above right. The Middle Path grip does not require that the thumb IP joint be extended, while the thumb MP joint be flexed. Could this be yet another way users find their own comfortable chopstick grips, outside of the demand of Standard Grip for a Caswellian thumb pose?

True learning aids

In most chopstick-using cultures, not being able to use the perceived, correct grip often reflects negatively on someone’s home environment. We have already explained earlier, and in Using vs Not Using the Thumb, how some of these perceived, incorrect grips came about. For instance, preschoolers are often coerced into adopting a non-standard grip early on, due to their inability to wield long and heavy chopsticks properly. These childhood habits often persist into adulthood.

Plenty of chopstick inventions have been created to address this issue of incorrect chopstick grip. These have been invented without an understanding of the variation of grip types. These inventions often run counter to their stated purpose. They mean to teach the correct grip. But their designs often prevent learners from making Standard Grip finger movements. We discussed these learning chopsticks at length, in the video shown below.

The video shown below discuss ergonomic marcosticks and training marcosticks alluded to earlier in this article, and at the end of the previous video. We created these based on insights gained from our research. These marcosticks may be helpful to those who want to learn or perfect their Standard Grip, despite possible anatomical constraints. You can print these yourself, if you have access to a 3D printer.

Two of these specifically address chopstick cramps. The first one is the our model H Finger Helpers. The second one is the model B Chopstick Buddies.

What the future may hold

There is still much for us to learn, from penhold research. That is a much better tilled land. In time we shall discover even more connections between penholds and chopsticks, and between handwriting and chopsticking.

For now, we’ll leave you with a podcast interview featuring Dr. Sassoon. She is 90 years old, as of the time of this writing. Yet she is still helping patients deal with trauma caused by constant criticism and stigmatism of having unconventional penholds. Here it is: How schools should be teaching children to write, with Rosemary Sassoon, from Tes Podagogy, plus the written companion piece.

#GripEquality

* note1: we elaborate on “Because finesse comes as a balance of compression vs extension power” in the “jello-lifting competition” section of YouTube episode on chopsticking from WorldFriends.

* note2: update 2021-08-09: We have finally amassed enough analysis of chopstick grips, that we can attempt to properly classify them using factors that identify orthogonal dimensions, in the description of any given chopstick grip. See the article Classification of Chopstick Grips.

* note3: as of Jan 2022, we have filed 3 US utility patent applications, and 2 US design applications on various training chopsticks. The two design patents have been granted. The first utility application has been granted and issued. The second utility application has been allowed, and will be issued in Feb 2022. The third utility application has not yet been examined. For details see: State of patent applications as of Jan 2022.